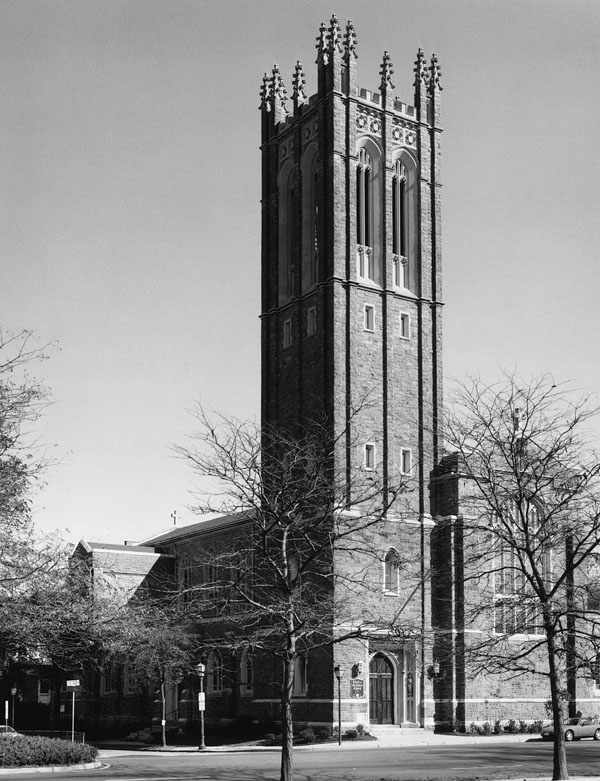

Christ and St. Luke's, The Church on The Hague Christ and St. Luke's Episcopal Mini-Cathedral (indeed, according to Episcopalian lore, the church becomes a cathedral when the bishop's in the building) is an architectural gem at the west end of The Hague. It was originally known as Christ Church and was built in the English Perpendicular Gothic Revival style. Construction was completed in 1910, and the first church service occured on Christmas Day of that year. The building's most recognizable feature is its tall granite bell tower topped with battlements and pinnacles. The church edifice in 2013:

The Gothic cathedral-like interior: christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan, primoid The busy and vibrant story-telling stained glass windows were made by Franz Mayer & Company of Munich, Germany (still in business), but their delivery and installation was delayed until after World War I ended in November, 1918:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan At the front entry, the corner stone of Christ Church, October 28, 1909:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan And on the other side of the entry, a corner stone citing the church's earlier architectural incarnations, dated 1800 and 1827:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Laying the corner stone (photo from the Harry C. Mann Photogrphy Collection of the Library of Virginia):

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Plus protection from a bolt from the blue, for as it is written, Thou shalt not tempt the Lord thy God — in this case, with a soaring bell tower:

See more photos from the church christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan But Mistakes Happen... First, a minor error from the church's beginning

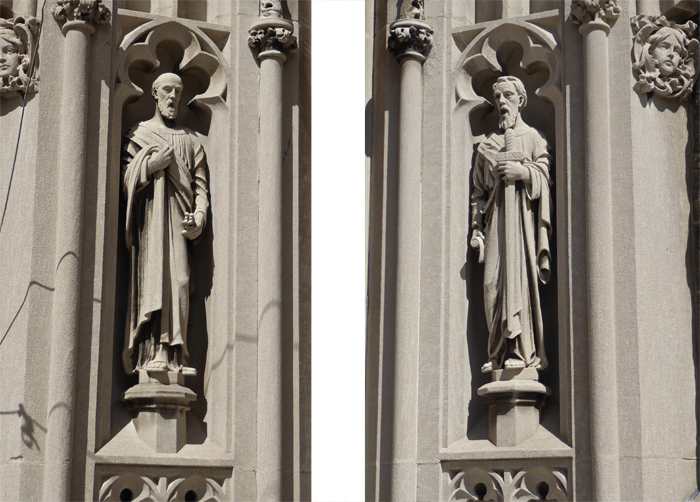

Stone carvings of the Apostles Peter and Paul guard the front entrance. How do we know they're Peter and Paul (and not, for example, Christ and St. Luke)? Because each apostle holds his traditional trademark symbol: St. Peter, the head disciple, to the left holding the keys to the kingdom, and St. Paul, the prolific scribe, to the right holding a scroll and the sword of the spirit. And therein lies the mistake. The sculptor got things backwards: Paul was supposed to be the baldy, while Peter, aka The Rock, was supposed to be the curly-locks he-man. While such a mistake may seem trivial today, it is a curious thing indeed considering that church artisans of yesteryear were typically quite scrupulous about upholding the traditions of Christian iconography. But maybe the sculptor, perhaps some artistic bigshot in New York City who had no respect for a booniesville like Norfolk, assigned the carving task to some callow and/or mischievous apprentice:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Next, a more recent mistake — maybe one in judgment? Nearly a hundred years later, the church had a grandiose idea, an ultra modernistic, $7 million, 15,500 square foot glass structure to be built right next to its Gothic Revival mini-cathedral, built in 1909. But neighbors in the Historic District didn't approve, so they went to court, and in 2008 they stopped it. Even though old houses in the Historic District should not be demolished willy-nilly, before the final resolution by the court, the church tore down its 100-year-old Guild House, which the new structure was to replace. The original idea was that the church would build a replica of the once busy-as-a-beehive old Guild House across the street from the new glass-and-steel edifice, but just like the new structure, the Guild House replica never materialized.

The church in 2004, with the stately old Guild House still intact behind it: christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Is tearing down a historic building any way to "maintain and restore" it?

Virginian-Pilot photo, February 27, 2008 christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Now, a mistake too big to correct? Or the emperor is naked, but who cares? Or what the hell (no pun intended) is going on? Or let's pretend the emperor always looked this way.

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Notice the difference on either side of the front door?

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan, primoid Or here, the loftily niched statue of Christ, the church's premier namesake. Notice the peculiarly bi-hued mortar joins around it, some white, some gray?

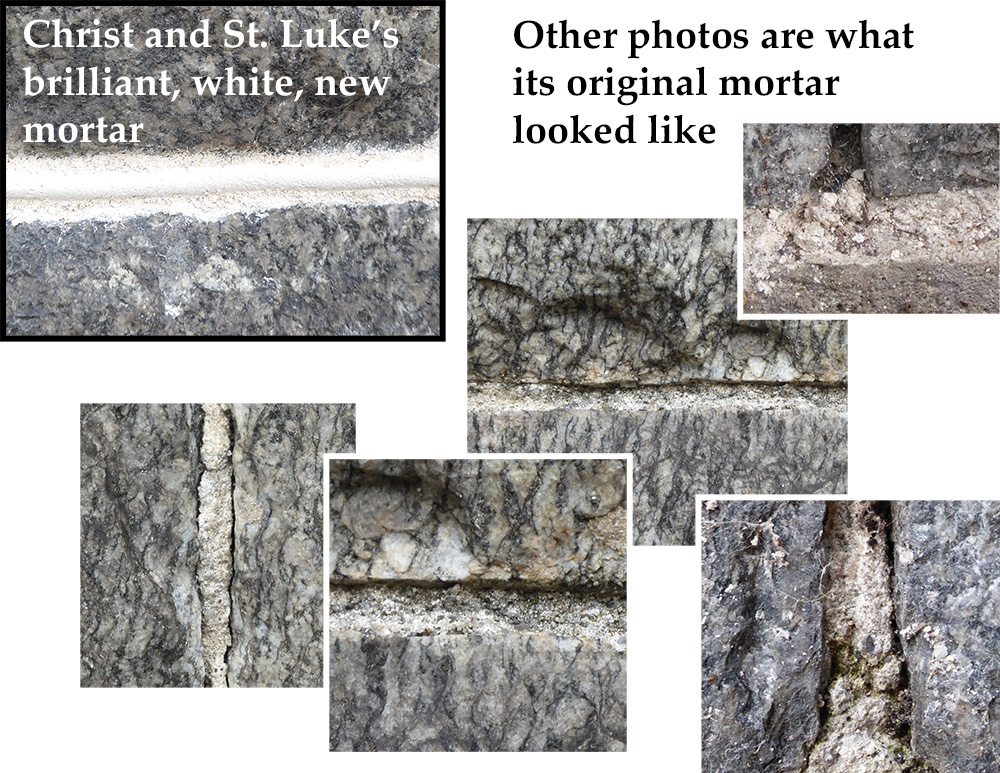

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan, primoid Restoration In 2018 Christ and St. Luke's commenced a multimillion dollar restoration project. It seemed like everything from the masonry, floor boards, pews, and stained glass windows to the pipe organ needed some kind of fixing. Stained Glass Speaking of the stained glass windows, didn't the church pay an alleged stained glass expert something like $10,000 in the late 1990s (like only 20 years ago) to tell it that its stained glass needed work, then pay a French company nearly half a million to remove and repair that stained glass, including releading it? Stained glass should only need releading every hundred years or so. Stonework Masonry repointing is a repair/restoration technique that involves replacing exposed worn, cracked, or otherwise degraded mortar between bricks or stone with new mortar. In 2018 Christ and St. Luke's Episcopal Church started looking a lot different because of repointing work done by a company that specializes in this kind of work. Looking different as in A LOT DIFFERENT! Different enough (since the building is a church) to call the expression "architectural sacrilege" to mind:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan, primoid Despite the fact that this problem was pointed out long before the job was completed, the masonry repointing contined. The claim was that, besides plugging up water leaks in the mortar, this new repointing was restoring the old church building to its original look. The claim was that because the building was previously repointed with an off-color mortar (sometime in the 1940s), the new mortar being put in is closer in appearance to the original mortar. But how close is close enough? Another claim was that the new mortar would patinate or otherwise darken over time to look more like the original. So does depending on Norfolk Southern's coal dust polluting qualify as a kind of moral hazard? And how long will it take that coal dust to make the new mortar match the old? Now the church has added a gleaming white security camera right next to its front door:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, primoid While the gleaming white new camera matches the gleaming white new mortar, the camera was placed on one of the areas of the masonry (right next to the front door) inexplicably left untainted by the look of the new mortar:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, primoid But then many more such untainted areas remain after the mortar "restoration" job is done:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, primoid How could this happen? — or are some mistakes just too big not to live with? The City of Norfolk has Historic Masonry Guidelines and an Architectural Review Board, but the City of Norfolk being run by the people who run the City of Norfolk (see more here), it chooses to ignore those guidelines, shirk its responsibilities, and pass the buck: "They have contracted a reputable company that does this type of work. They are following the Secretary of the Interior Standards for repointing.* The grout will patina out over time and be less bright. Repointing is considered 'maintenance' and does not require a COA from the ARB. I know they are getting Historic Tax Credits for this project so VDHR is reviewing this project" — Susan McBride, Principal City Planner, Historic Preservation Officer * Are they really following the standards? See those standards? And how could the church itself let this happen? Any large masonry project should include a sample demonstration (typically done on a small, out-of-the-way area of the stonework) for the customer can be sure the result will look right. Who decided such radical change in the appearance of the mortar as this was acceptable?

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid Lotta scaffolding. Imagine what a do-over would cost?

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid

Consider the Rules of Proper Repointing See the Federal Government Mortar Match Standards "The sand must match the sand in the historic mortar. The color and texture of the new mortar will usually fall into place if the sand is matched successfully."

No mystery what the original mortar looked like It's hiding all over the church, only and inch or so beneath the repointing mortar. Surely it was looked at — wasn't it? — before someone, presumably some committee, decided to repoint it with that bright white new mortar. See the photo of Christ and St. Luke's mortars below. Consider the granular texture of the original mortar due to the mix of different sizes and shades of sand found in it compared with the smoother, more homogeneous-looking, bright white new mortar: |

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, mortar, masonry, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid, norfolk.gov

.jpg)

The thing is, proper repointing work includes matching color, texture, composition, and strength of the new mortar to the old. Federal government standards and even the City of Norfolk's Historical Guidelines, which are supposed to apply to old buildings located in Historic Districts like Ghent, clearly state this. The whole idea of Historic Districts is to maintain the original appearance of old buildings located in them. And the City of Norfolk is supposed to enforce its guidelines in these districts. Excerpt from the City of Norfolk's guidelines: The most common work to be done on brick or stone walls is repointing. This should be done with a mortar similar to the original in texture, color, composition and strength. Execution of mortar joints in width, style and profile should match the existing. Caulk or Portland cement (unless it is the original mortar material) are not appropriate for use on historic masonry walls because they are stronger than the historic brick and can cause the brick to crack or spall. But the old church's entire stonework has already been altered (err, repointed), so how likely is it that this costly flub will be corrected? The granular original mortar, with a conglomeration of multisized, multihued sand grains, can still be seen in places like this, where it is not covered with repointing mortar. And its appearance will always available, anywhere else on the building, just beneath the new repointing mortar:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Closeup of the smoother new repointing mortar. Does the sand look anything like the sand in the above photos? Is sand even visible here? This is one of the many places where the new mortar was put in with adjacent old mortar left in place:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Photo of a mortar joint (between sandstone blocks) on a "historic revival" house built in Ghent in 2015. Note the varied colors and sizes of the sand visible in the mortar of this new house. Even this residential mortar looks more like the church's original mortar than does the repointing mortar. Of course new mortar can be matched much more closely to old mortar than what is seen with this church:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, aria mcclellan, richmond primoid The Obvious Difference Newly repointed west side of the building (left) next to the not-yet-repointed front (right):

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan Appearance altering repointing mortar creeping up the bell tower:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, stained glass, andria mcclellan If the purpose was to restore the mortar to its original look, why swere portions of the old, darker repointing mortar left in place amidst the new, lighter mortar (here on courtyard side of the church)? They call this patchy-looking work finished? (Stockley Gardens side of the building):

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, mortar, masonry, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid Court yard side of the building:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid Black and white photo of the church from 1979, looking like it used to:

The City of Norfolk has allowed patchy, faulty masonry "restoration" to blight other historic landmarks too (here, the venerable eighteenth-century Moses Myers House in central downtown):

|

January, 2019, Christ and St. Luke's with its brand new look:

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, mortar, masonry, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid, norfolk.gov

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, mortar, masonry, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid, norfolk.gov

christ and st. luke's, norfolk, mortar, masonry, andria mcclellan, richmond primoid, norfolk.gov